In today’s fast-moving geopolitical world, can the President of the United States start a war without Congressional approval? This question has become increasingly urgent as modern conflicts unfold faster than the legislative process can keep up. While the U.S. Constitution explicitly grants Congress the sole authority to declare war, recent decades have seen a surge in military actions initiated solely by the Executive Branch.

From the Korean War to targeted strikes in the Middle East, presidents have routinely used their Commander-in-Chief powers to deploy troops or launch airstrikes without a formal declaration of war. The line between defensive action and unapproved military aggression has become increasingly blurred.

In this article, we’ll explore:

-

The constitutional limits of presidential war powers

-

Legal loopholes like the War Powers Resolution and AUMF

-

Real-world examples from recent U.S. history

-

What happens when Congress and the President disagree on war

Whether you’re a law student, political analyst, or curious citizen, understanding how U.S. war powers really work in 2025 is critical in grasping the balance between executive authority and democratic accountability.

1. Constitutional Basis: Why Congress Declares War

The U.S. Constitution grants only Congress the authority to declare war, reflecting the Framers’ intention to prevent unilateral, unchecked military actions by any president. From the Revolution through World War II, Congress formally declared war 11 times, setting a clear precedent .

2. The Evolving Gray Zone: Military Actions Without Formal Declarations

Although formal war declarations are rare today, Congress authorizes numerous military operations through resolutions—over 100 times post–World War II. This has created ambiguity around when a president may act independently .

Key Examples:

-

1950, Korea: President Truman bypassed Congress by securing a UN mandate and labeling the conflict a “police action.”

-

1990, Gulf War: H.W. Bush asserted the authority to deploy troops even without Congress’s approval—but Congress passed a joint resolution authorizing the operation.

No modern U.S. president has formally declared war alone, but executive military initiatives continue through alternative legal paths.

3. Commander-in-Chief: What Powers Does the President Have?

Legally, the president serves as the Commander-in-Chief, granting broad wartime powers, such as:

-

Deploying U.S. troops

-

Launching invasions or military incursions

-

Conducting intelligence operations

-

Ordering nuclear strikes

These powers have been expanded or limited over time:

-

War Powers Resolution (1973): Requires congressional approval within 90 days of military engagement; beyond that, U.S. forces must begin withdrawal within 30 days .

-

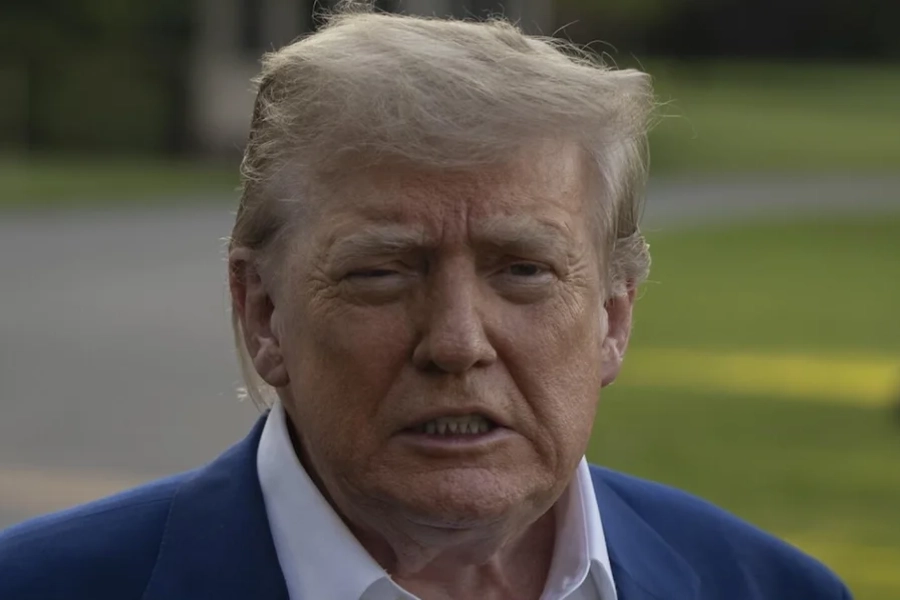

An exception allows the president to act in emergencies and defensive responses—a claim used by President Trump during the 2017 Syria strikes.

-

The 2001 AUMF empowered presidents Bush and Obama to take military action against terrorist entities globally .

4. Ongoing Controversies: Iran, Greenland, Panama

Iran (June 21, 2025)

The U.S. struck Iranian nuclear facilities without Congressional approval or a formal declaration of war. Officials cited the War Powers Resolution and imminent threat doctrine. Congress responded with resolutions aiming to restrict this military expansion .

Greenland & Panama Canal Scenarios

-

Greenland (part of Denmark): A U.S. military intervention here would face serious legal hurdles and widespread public opposition.

-

Panama Canal: Now under Panamanian sovereignty (since 1999), any U.S. military activity would be legally complex and diplomatically sensitive.

5. Why Presidential “First Strikes” Persist

Although constitutional texts mandate Congressional war declarations, real-world practice favors quick executive decisions paired with post-factum legislative approval. Tools like the War Powers Resolution and AUMF facilitate this modern approach to warfare.

Final Takeaway

-

Legally, presidents should not declare war or launch prolonged conflicts without Congressional consent.

-

Practically, mechanisms like UN mandates, AUMFs, and War Powers Resolution loopholes enable swift presidential military action.

-

While the Constitution emphasizes separation of powers, today’s world demands fast responses, which often tilt the balance toward executive action.

Can the President go to war without Congress?

Technically, no. The Constitution states that only Congress can declare war. However, presidents have often used executive powers and Congressional resolutions to initiate military action without a formal declaration.

What is the War Powers Resolution?

The War Powers Resolution of 1973 limits the president’s ability to send U.S. troops into combat without Congressional authorization. It requires withdrawal within 90 days unless Congress explicitly approves continued involvement.

What is the difference between war declaration and military action?

A declaration of war is a formal, legal statement by Congress. A military action, such as a targeted strike or troop deployment, can occur without it under certain conditions, particularly if justified under the War Powers Act or AUMF.

What is AUMF and why is it important?

AUMF stands for Authorization for Use of Military Force. Passed in 2001, it gives the president power to use force against any nation or group responsible for terrorist threats—without declaring war. It has been used to justify U.S. military operations globally since 9/11.

Has any president ever declared war alone?

No U.S. president has ever unilaterally declared war. All formal declarations have come from Congress. However, many presidents have initiated military campaigns independently, especially after World War II.

Can Congress stop a military action by the president?

Yes, but it’s difficult. Congress can vote to cut military funding or pass resolutions to limit war powers—but the president can veto them. Overriding a veto requires a two-thirds majority in both chambers, which is rare.

What are the consequences of launching military action without Congress?

Potential consequences include legal challenges, international backlash, constitutional crises, and even impeachment efforts, depending on the scale and impact of the action.