In an alarming development revealed in a June 2025 report by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Inspector General, a hacker linked to Mexico’s infamous Sinaloa drug cartel allegedly exploited public surveillance networks and mobile data systems to identify, track, and indirectly assist in the elimination of FBI informants tied to the investigation of El Chapo Guzman — the notorious kingpin of global narcotics trafficking.

The findings raise serious questions about the vulnerability of U.S. law enforcement operations abroad, particularly in jurisdictions where criminal organizations wield high levels of technological sophistication and systemic corruption.

How the Cartel Exploited Technology

According to the DOJ report, in 2018, an individual connected to the cartel informed an FBI case agent that a hacker had been contracted to surveil U.S. personnel in Mexico. The hacker successfully identified the FBI’s Assistant Legal Attaché (ALAT) in Mexico City and used mobile number tracking, call data, and GPS information to monitor the agent’s movements.

Additionally, Mexico City’s vast surveillance camera system was tapped to visually track the agent and identify individuals he met with — several of whom were later intimidated or killed, presumed to be FBI sources or cooperating witnesses in the ongoing case against Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera.

What the DOJ Report Reveals

The DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General issued a critical assessment of the FBI’s response to what it terms “Ubiquitous Technical Surveillance (UTS).” This refers to the expanding global network of CCTV, mobile data aggregation, and commercial metadata exploitation — tools that are increasingly falling into the hands of both nation-states and organized criminal groups.

Key Failures Highlighted:

-

Insufficient Red Team strategy: The FBI’s internal cybersecurity task force failed to anticipate cartel-level technical threats.

-

Lack of holistic assessment: The Bureau did not adequately map out the full scope of operational exposure in foreign environments.

-

Training gap: Field agents lacked appropriate education on digital exposure, metadata exploitation, and surveillance countermeasures.

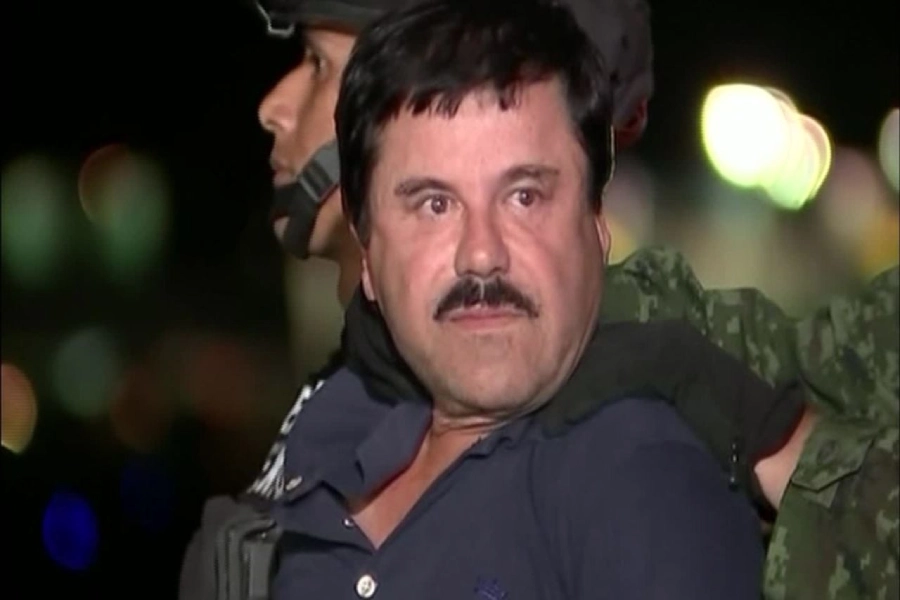

Who Is El Chapo Guzman?

Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera, widely known as El Chapo, was the leader of the Sinaloa cartel, one of the most powerful and violent drug trafficking organizations in the world. He was captured and extradited to the United States in 2017 and is currently serving a life sentence in a high-security prison for drug trafficking, money laundering, and murder conspiracy.

Despite his imprisonment, Guzmán’s criminal network remains active, and the cartel continues to leverage advanced technology for intelligence gathering, logistics, and — as this report shows — counterintelligence and retaliation.

Legal Implications & Policy Analysis

1. Violation of International Law

The use of state infrastructure (like citywide surveillance cameras) to target law enforcement agents of a foreign nation represents a serious breach of international norms, and potentially, bilateral treaties between the U.S. and Mexico.

2. Data Privacy and National Security

This case illustrates the growing national security risk posed by commercial data brokers and weak telecom regulations, which allow adversaries to buy or extract metadata without hacking devices directly.

3. Accountability and Institutional Response

The DOJ’s report emphasizes the need for:

-

Inter-agency coordination

-

Operational security audits

-

Legal reforms that regulate access to surveillance systems and personal location data

Lessons for Law Enforcement & Intelligence Agencies

This case underscores the urgent need to:

-

Upgrade OPSEC (Operational Security) protocols for agents operating abroad

-

Limit personal data exposure through stricter mobile device management

-

Partner with host governments to audit and restrict access to surveillance tech

-

Train field agents to identify signs of cyber targeting and counter-surveillance

What Makes This Case Unique?

-

First documented case where digital surveillance directly led to multiple source deaths

-

Demonstrates the ease with which non-state actors can weaponize metadata

-

Highlights the inadequacy of current U.S. cyber countermeasures in foreign intelligence missions

FAQ

Who is El Chapo Guzman?

El Chapo Guzman, born Joaquín Archivaldo Guzmán Loera, is the former leader of the Sinaloa cartel. He was captured in 2016, extradited to the U.S. in 2017, and sentenced to life in prison in 2019.

How did a hacker help the Sinaloa cartel?

A hacker reportedly hired by the Sinaloa cartel used mobile metadata and public surveillance cameras to track an FBI official in Mexico. The information was then used to identify and eliminate FBI informants.

What is Ubiquitous Technical Surveillance (UTS)?

UTS refers to the widespread use of surveillance tools such as CCTV cameras, phone location data, Wi-Fi signals, and financial records to track individuals. The DOJ report suggests UTS is now a major vulnerability for law enforcement.

Is El Chapo still running the Sinaloa cartel from prison?

While El Chapo himself is incarcerated in a U.S. supermax facility, the cartel continues to operate. Leadership is believed to have passed to his sons, known collectively as Los Chapitos.

What is the U.S. government doing to prevent future hacks like this?

The DOJ and FBI are now restructuring their cybersecurity and surveillance strategies, including increased training for field agents, enhanced metadata protections, and interagency red teaming.

What laws were possibly broken in the hacking of the FBI agent?

Potential violations include:

-

Wiretap Act (18 U.S.C. § 2511)

-

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

-

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) implications

-

Violations of Mexican constitutional privacy protections

Conclusion

The El Chapo Guzman case, already a defining narrative in the global war on drugs, has now become a cautionary tale for digital-age espionage and law enforcement exposure. The DOJ’s 2025 findings reveal how data exploitation, not just firepower, is now central to cartel operations.

Without significant changes to how the U.S. approaches operational cybersecurity in foreign environments, intelligence agencies may face further deadly consequences from adversaries who are increasingly digitally capable and ruthlessly strategic.